As the title indicates, in the last two posts (Part 1 and Part 2 – and also be sure and check the comments from others) I’ve described the conundrum of organizing agile teams at scale, and said I’d provide some additional input from others along with some recommendations.

Should the Agile Enterprise Lean to the Feature Team Approach?

Given the advantages and disadvantages to each approach – essentially the balance of immediate-value-delivery vs. architectural focus and potential for reuse, the agile enterprise clearly leans towards the feature team approach, as there can be no question on the immediate value delivery velocity benefits and the focus of the teams.

However, as we’ll see below, the answer is not that simple, and it’s likely that a more balanced approach may be required.

Mike Cottmeyer opined:

” Our first really important decision when thinking about how to scale agile is determining if the feature team approach will work or if we should consider a component team model. Feature teams are THE starting place for agile organizations. They are loosely coupled and highly cohesive and their inherent independence from the rest of the organization makes product development significantly faster and easier to forecast.

That said… many organizations are dealing with issues that make the feature team approach difficult to implement at scale. These companies are developing products that are actually systems of systems. Integrating disparate systems… disparate technologies… disparate build environments… disparate locations… disparate cultures… and disparate organizational politics into a single integrated feature team is not always advisable for even a moderately sized development shop. For these organizations… the component team model represents a viable scaling alternative.

Yes, there are increased coordination costs associated with running large projects through component teams. Hopefully those costs are offset by the value of multiple products leveraging those commonly shared components. Many organization will have to take a hard look at the feature team approach and examine at what scale the feature team approach will break down… because at some scale they WILL break down. “

Even then, the Line is Blurry

Even in light of this advice, we must also recognize that features and components are both abstractions and the line is not so clear. One person’s feature may be another’s component.

For example, TradeStation Securities builds an on-line trading system where “charting market data” is a key capability for the trader. A few collocated agile teams work together on the charting function. They are some of the world’s foremost experts in charting real time data of this type. On the surface, that looks like an excellent example of a feature team, as charting certainly is a major feature of the system.

However, when new online trading capabilities are developed, such as “trading foreign exchange currencies (Forex),” new chart functionality must be added. However, driving this new chart functionality are major components such as streaming data, account management and interfaces with Forex exchanges. Is the new feature value stream described as “trading Forex all the way through the specialty chart function?” If so, that would make an obvious vertical feature stream and the teams might reorganize by taking some members of each component team and create a new vertical feature team for Forex trading.

Or, is the feature “trading of Forex” plus “charting Forex”, in which case the charting team is already organized appropriately? Is the charting capability a feature set or a component? Both? Does it matter what you call it?

Even in the case where it is clear what you call it, is a feature team always the best choice? Keith Black, VP of TradeStation Technologies, notes:

“When we first interviewed Scrum coaches their view of Agile was solely focused on feature teams, this threatened to kill the initiative. Online trading requires a great depth of expertise and industry knowledge at many different levels. We could not reasonably form feature teams that included members from every component area. For one we’d have to increase our staff, and secondly the feature teams would be too large if they covered every facet of the trading process end to end.

Therefore, for our transition to Agile we organized around component teams and through maturity we are now in special cases putting together feature teams where it makes sense. This works for us because feature teams are excellent at driving an initiative through completion.

However, in some cases they still don’t make sense. For example, if you have twenty feature teams and they all rely on a common component, such as a time-critical online transactional processing engine, it may be inadvisable to have 20 different teams sticking their hands into this critical component. Rather, you might choose to have these changes controlled by a single Agile component team that can broker the needs of the 20 teams and make sure they don’t step on each other’s toes, or jeopardize areas they don’t understand by making changes for their particular features.”

So The Answer is Likely a Mix

In the larger enterprise where there are many teams and many, many features, and systems that are in turn composed of system, the answer will likely be a mix of feature teams and component teams. Indeed, even in the modest-sized agile shop, a mix is likely to be appropriate. Ryan Martens, founder and CTO of Rally Software (as agile as an organization as any that I am aware of) sketched the following, five-agile-team org chart and its “feature paths” for me:

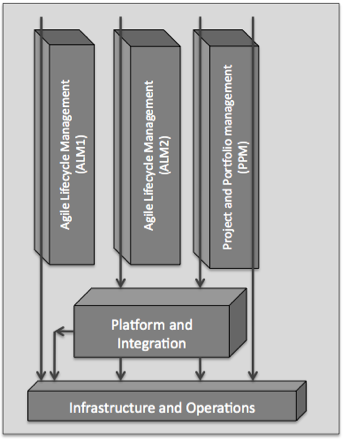

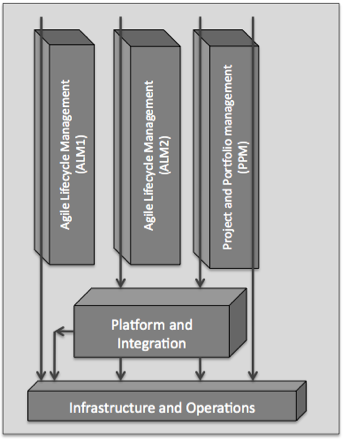

Figure 1: Five-team agile organization with various feature paths noted.

Ryan went on to note:

“While we don’t think of it in these terms as such, three of these teams (ALM1, ALM2 and PPM in the top) would be readily identifiable as feature teams. One, (Infrastructure and Ops, on the bottom)” is clearly a component team. I don’t know what you’d call the one (Platform and Integration) in the middle, because it sometimes originates it’s own features, and sometimes is simply a supportive component for other features.”

He concluded with some sound advice:

“What I would recommend is that you don’t get too hung up on the labels and the organization at the start. We think of maturity in stages: Flow, Pull and Innovate. In Flow, it’s about getting organized into agile teams and getting the value stream flowing in an agile manner. For Pull, its about leaning the work in process and having backlog maturity so that teams can pull from the backlog and implement in an order that makes the most technical and value sense. In Pull, I’d think a feature team could be a logical evolution for many. However, it’s getting started in Flow that is most critical and hardest step, and if you have to reorganize the enterprise before you begin, you may never begin at all.”

Recommendation: Lean to Features, Accept a Mix and Optimize Near Term for Collocation

Based on all this input and well-articulated arguments from both sides of the feature teams vs. component teams debate, what is my recommendation?

Interestingly enough, at real scale (think 30-40-50 teams), features are such spanning items, that this whole argument can become almost silly, and those cases, a broader “program based” (groups of teams collaborating) organization model (not unlike the charting teams feature/component pod above) must be considered.

But in the more typical, modest size enterprise or business unit (5-10 teams), my recommendation is to apply feature teams wherever practical, but to optimize neither for features nor components per se, but to optimize around collocation. Pick feature teams if they are already collocated. Pick component teams if they are already collocated. The communication, team dynamics, continuous integration support, and velocity benefits of collocation are likely to far exceed the benefits of the perfect theoretical organization, especially when the benefits of one approach vs. the other are not always so clear, as the various opinions indicate.

As your agile organization matures, you’ll be so competitive that you’ll have lots of opportunity to inspect and adapt your model and evolve your organization in a way that makes sense to you. But in the meantime, maybe nobody will have to move!